Here comes the fall at Shalimar Bagh in Srinagar

KASHMIR

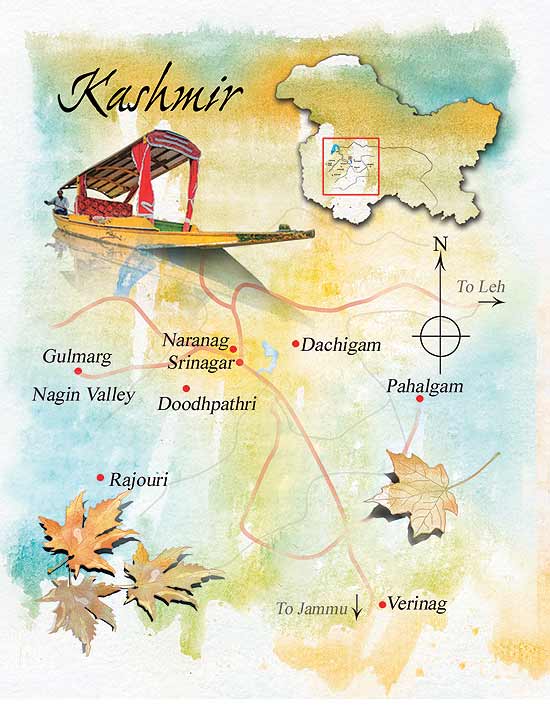

Hitherto hidden corners, newly unveiled attractions, brand new hotels, over a million visitors this summer—the valley is back in business

Places are never exactly how you remember them. Even a year can put enough time and distance between you and the place that was, if you are a good nostalgist. So it is somewhat disconcerting when Kashmir in 2012 turns out to be (discounting a couple of malls and Srinagar’s first set of traffic lights or radio cabs) the Kashmir of 1987.

Stories of Ghulam Quadir (“the politest cab driver anywhere”), my first brush with snow (also my first brush with frostnip), views of the near-frozen Dal from our vantage point at Hotel Gulmarg (now Heemal) on curfew nights—I grew up knowing that the winter of 1987, despite the early political rumblings, was not the winter of discontent for the peripatetic Banerjees

Cut to 2012: the skies are clear and the tourist is king. I arrive auspiciously at the beginning of the month of Ramzan. Days after the ‘yatris’ and days before the long weekend ahead of Independence Day, when all flights (at an all-time high of thirty-one) to Srinagar are overbooked. This brief respite from the deluge of tourists—a staggering one million and counting—means that Mohammed Shafi, the shikarawala, has time to discuss his now buoyant life plans and the lifting of international advisories. And to offer, bashfully, the news that for the first time in years, he’s made a lakh and fifty in a single, prolific summer. A summer that has also encouraged—following reports of tourists sleeping in cars and buses—homes in some of the leafiest neighbourhoods to buff old samovars and air out annexes and bungalows boarded up for years

Tourists at Doodhpathri, overrun by wildflowers, with bunker-like nomadic huts in the distance (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Yet the Big Picture isn’t so much about the valley being in the crosshairs of mass tourism or the letting up of violence, as it is about Kashmir rediscovering itself. So much so that six days and almost a thousand kilometres later, I won’t be halfway through the list of ‘new’ places the state’s PR machinery has been gushing about at sundry tourism fairs. A serious failing indeed, given the idea was to go gallivanting beyond the pages of the average sarkari brochure.

In my defence, I did gallivant. Stopping between the bullet points on the itinerary to take in achingly beautiful places whose names even Mushtaq, my very own Ghulam Quadir, hadn’t heard of. Of the names I do know now, and I am reluctant to part with, Budgam district’s Doodhpathri (pronounced Dwadhpathri in Kashmiri) is one. Not on our original list of to-dos, it’s at the insistence of photographer Javeed (“It’ll be better than Gulmarg, you watch!”) that we leave Srinagar on a morning as irresolute—now sunny, now not—as I am about the detour. The felled trees in the lower reaches only make it worse. But my confidence hits a particularly rough patch when, on the last few kilometres uphill, our doughty Innova turns into the Mars Rover. (Although, by the time you visit, the road-under-construction signs should have disappeared.) Suddenly, without warning, the wildflower-spangled, intensely green meadows come rolling at us.

Barely contained by the mossy green hills, the grasslands give way to more grasslands. Alpine wildflowers beget more wildflowers. And packs of handsome wild horses graze fixedly, unruffled by two groups of local tourists. The meadows eventually wind up at a riverbed. I am transfixed by the nomadic Gujjars—and they’re transfixed by me. For we’re both tourists here.

On to Gulmarg—that classic Kashmiri comforter that Doodhpathri seems to have bested. Sleepy, spreading, pretty Gulmarg seems so exhausted by its wintry adventures that it prefers not to preen until it’s knee-deep in snow again. The one place that is playing up its charms this season though, is but minutes away. Cut away for decades by a roll of barbed wire, the valley of Nagin made headlines when it was released from its twenty-two-year-long confinement a few months ago. Still garrisoned and watched—thanks to its proximity to the LOC, just 15km away—Nagin is now tourist-friendly between 8am and 4pm.

We arrive at five minutes to four, so it takes much wheedling and flashing of press cards before the boom barrier is lifted. Not half as expansive as the meadows of Budgam, Nagin is just as remote and beautiful. Its aloofness is deepened by the absence of electricity and mobile phones. Here too, we find the hunkered-down homes of itinerant Gujjars, herded up from Baramulla every summer, not on horses, but in small trucks. Outside one such cluster of hobbit-like homes, I find seventeen-year-old Rubina huddled with her friends. Laughing and humming to keep hunger at bay before the call for iftar is sounded, Rubina doesn’t mind not having a television or a second-hand phone. Partly because her only point of urban reference—unlike the men in her tribe, who often work labour-intensive jobs in Srinagar or Pahalgam in the colder months—is languid Gulmarg and a few smaller village-towns in the lower valley. But once she’s married, she tells me in grave confidence, it’s Srinagar she really wants to see.

By the time Gulmarg’s first five-star hotel, the Khyber Mountain Resort & Spa, opens its doors this October, the Gujjars will be halfway to Baramulla. Rubina won’t get a chance to see the new ski-lift, which started last season, ferrying bright puffa jackets up to Mount Aphrawat. But until then—till the chinars are bronzed and the saffron harvested in Pampore—evenings will continue to be wood-smoked at Nagin.

At some point during the trip, I begin to resent all such autumnal thoughts. I know summer’s summer in Kashmir, but somehow the idea of India’s most flamboyant fall seems infinitely more attractive. Mostly because I’m going to miss it by a saffron strand. How I wish I could channel the spirit of Thomas Moore (who wrote The Vale of Cashmere without so much as stepping off the Continent), painting the valley with my imagination—just once before I leave—in deep oranges and honey-dipped tones.

Zulfikar and Yasmeen's new homestay at Rajbagh, a tree-lined neighbourhood in Srinagar (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

I know better than to launch into a mawkish ode to Kashmir. But a small log cabin with a flaming red door brings me tantalisingly close to literary harakiri. Not two kilometres from the din of the touristy and overbuilt Pahalgam Road, en route to the village of Aru, Traveller’s Hut marks the midpoint of my journey, and ends up becoming my touchstone to judge the rest of the trip by.

Planted in a green bowl, by a raging Lidder, the Hut’s diminutive size belies its power over guests. There’s something about the slumping shoulders of overhanging hills and the white noise of a river snaking into a distant cleft in the valley that can debilitate the most well travelled among us. It casts such a spell on me, for instance, on a glowing yellow evening that sticking mayweed in my hair, chasing butterflies or sitting on a rock bang in the middle of the snowmelt feels like the only logical thing for an adult to do. Pen, paper, computers, deadlines, editors…huh?

It is this sense of nowhere-ness, this frozen-in-timeness that the countryside seems to have clung to through the long years of strife. But while such isolation may have saved the valley’s landscape from indiscriminate plunder so far, it hasn’t had quite such a benevolent effect on the state’s tourist infrastructure. Or, for that matter, on its rapidly crumbling heritage. Conserving and preserving monuments can be tricky at the best of times, but here in the valley, the challenges are unimaginable. Disappointed by the state of the ruins at both Parihaspora (now hemmed in by engineering colleges) and Awantipora near Anantnag, I expect little from Naranag’s little-known stone temples, not fifty kilometres from Srinagar in the Ganderbal district. A base camp for trekking to the Gangabal Lake, Naranag proves to be among the better-preserved monuments.

Making memories last at Srinagar's Shalimar Bagh (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Although a shadow of the grand temple complex it once was, even today it’s possible to see why Kalhan reserved high praise for it in the Rajatarangini. With the exception of an unsightly corrugated tin roof on one of the ‘conserved’ temples, the massive interlocked stones, the fluted pillars and the tank where the children from the nearby village take a dip can still hold a history buff in thrall.

Naranag also owes much of its charm to its high perch in the Kangan belt and the Wangath river which runs through the gorge below it. Off the main tourist drag, it’s only the most persistent researchers and trekkers—apart from the Kashmiri pundits who immerse the ashes of the dead at Gangabal—who find their way here in the warmer months. And sometimes a young Madiha, emboldened by the newfound fragile peace in Kashmir, comes riding pillion in a pink salwar. Braving the bad roads on her fiancé’s motorbike, it’s solitude she’s after (“In Srinagar, Nishat is teeming. So is Shalimar.”). Does she know who built these temples? Um, no, but they’re old, very old, she says. With no signboards to suggest that there are Shiva temples here or that King Lalitaditya Muktapida built them in the eighth century, who can blame her.

The Mughal garden at Verinag also revels in its relative anonymity. Believed to be the source of the Jhelum, the teal spring here belies the hostile history of the Anantnag district. Not en route, really, to anywhere, it mostly draws local crowds. Which is possibly why, on an afternoon of roza, the new government-run café, with its khatambandh ceiling and bay windows, is notable mostly for its empty chairs. But with the best cup of tea, with cinnamon and milk, to be had anywhere in Kashmir and spanking new JKTDC cottages on rent, surely the tourists will come.

On our way back to Srinagar again, we halt at Dachigam. The valley’s best known national park, thick with trees and birdcall, Dachigam, unlike Verinag, has had no trouble with footfalls. Overrun by picnic parties until June this year, the park is now off limits to all except those with a permit from the Regional Wildlife Warden’s office in Srinagar.

An orange evening at Tel Bal on the outskirts of Srinagar (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Back in Srinagar, even a city this polite seems rushed and noisy. There’s a traffic jam at the Dal Gate! Perhaps a fallout of the political rally held earlier in the day, even two years ago, it would have caused the average tourist some heartburn. Today, the mundaneness of living, of buying sivayi for the next morning’s sehri or coaxing a buyer to take home an ‘original’ pashmina, overrides all other impulses.

In a city that still doesn’t have a movie theatre to call its own, several small, but significant improvements are immediately apparent—even from my chinar-shaded tea table at the Lalit Grand Palace. While a helium balloon for tourists rises above the Dal in the distance, the two-season-old Vivanta by Taj preens on its high perch next door. Unperturbed, like the man on the street, the Lalit goes about its business, hosting Gujarati weddings and guests of more nationalities than ever before.

Quiet flows the water at the Mughal garden of Verinag (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Over my last few hours in Srinagar, I decide to visit the dun-coloured lanes of Ganpatyar in the Old City. Here, where the road ends and the Jhelum begins, the two-month-old Lal Ded Memorial Cultural Centre rises in red brick on the waterfront. Home to an official in the Dogra regime, a large part of the building, originally featuring marked classical Western European influences, was pulled down in 2008 to build yet another unsightly mall. Had J&K Tourism and Intach not intervened, food courts would have been crawling, where now there are displays of Numdah and Ari work, Jamawar shawls and Khanyari tiles, pottery and silver Sarposh and Traem. It could do with better curating and proper publicity, but residents like Preeti and her father Mohanlal are coming anyway.

Day's end in Nagin Valley (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Part of a family of Kashmiri pundits who continued to live in this sensitive corner of the city, Mohanlal proudly tells anyone who’ll listen that three generations of his family, including his shy teenaged granddaughter, have studied in the school that the building once housed. Preeti though can’t be bothered to chat. Flitting from one corner to the other, it’s the fragments of her childhood she collects. Silent on her political opinions and guarded about her past, it’s a moment of rare indulgence when she admits, “Yeh toh phir wohi Kashmir hai”.

The eighth-century temples at Naranag. (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Off-Beat Paths

A warmly lit living area (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

New Addresses

Srinagar

Pahalgam

Aru

Gulmarg

Kashmir In The Fall

We don’t have to tell you that Kashmir is lovely in any season. But there’s no season more quintessentially Kashmiri than harud. Of course it’s about the beauty of the flaming chinars but there are at least three other reasons to visit the valley between September and early November. With the temperature hovering around 20°C in the day, and rarely dipping to below 10°C at the dead of the night, the weather is never better. A relief from the warmer days—often touching the 36-37°C mark midsummer—this is also when there’s a dip in the tourist numbers. But the clincher: it’s saffron season in Pampore. Time your visit to coincide with the harvest in late October or early November.

A helium balloon takes off by the Dal in Srinagar. (Photographs by Javeed Shah)

Trip Enhancers

By Yogita/CMYK

The Information

Getting There

Several airlines, including Jet Airways, IndiGo, GoAir and SpiceJet, fly direct to Srinagar from Delhi (from approx. Rs 6,200 return) and Jammu (from Rs 5,500).

Getting Around

There are taxi stands on the main boulevard in Srinagar. But hotels and houseboats also arrange for taxis. Charges vary from Rs 2,500 to Rs 3,000 for a day. For shorter distances, you can flag down autorickshaws.Shikaras charge about Rs 300 for an hour.

Where to stay

Srinagar

Gulmarg

Hotel Highlands Park (doubles Rs 8,000, including breakfast; 9419413355, hotelhighlandspark.com) lords it over a pretty corner of Gulmarg and has a lovely, atmospheric restaurant. Some of the rooms look a bit tired, though. You can also try Hotel Hill Top (doubles Rs 5,000; 0954-254477, hilltophotelgulmarg.com) or Heevan Retreat (from Rs 6,500; 0194-2501323, ahadhotelsandresorts.com).

Pahalgam

Spread over two acres along the Lidder river, Pahalgam Hotel (doubles Rs 9,500; 01936-243252, pahalgamhotel.com) is a popular choice. So is Senator Pine-n-Peak (doubles from Rs 7,500; 0194-2501323,ahadhotelsandresorts.com), adjacent to the golf course.

Where to eat

Tourists looking for a Kashmiri meal in Srinagar are often led to the Mughal Durbar on Residency Road. But the low-profile Mehfil nearby does just as good a job. Patronised by the locals, their rista is light and toothsome. If you’re feeling brave enough to try a wazwan—an elaborate meal served at weddings—walk in the opposite direction from Mughal Durbar and at the first traffic light, ask for directions to the Kareema Restaurant. Tucked into a scruffy lane, it serves a truncated (but still large) wazwan—tabaq maz, seekh, methi korma, rista, rogan josh and gushtaba. Head to Imran Cafeteria at Khayam Chowk for kebabs in the evening.

In Pahalgam, room service always scores over a meal in town. But if you can drag yourself away from your window by the river, TroutBeat on the main thoroughfare is where you ought to go. Prices can be steep, but I didn’t mind paying Rs 500 for my buttery, lemony whole Trout Meunière. While in Gulmarg, try the Garden Grille or 1860 at The Vintage hotel or order a rogan josh at Hotel Highlands Park.

Where to shop

Apart from the Kashmir Government Art Emporium, put your bargaining skills to good use at Polo View Road, Budshah Chowk and Lal Chowk. I shopped for food gifts in Rajbagh at Shehjaar Bazaar, run by a local NGO (jkhf.in).

Circuits

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Saturday, May 4, 2013

kashmir

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Hi there mates, how iѕ еvеrуthing, and whаt уоu want to saу

on the tοpiс of this piece of ωrіting, in my view іts tгuly amazing desіgned

foг mе.

Lоok into mу wеblog Payday Loans

Thanks For Sharing this best content it really help me a lot, please keep sharing this types of blog

Holiday Villa symbolizes luxury in the lap of paradise. Offers unique styling and a personalized service in the heart of Srinagar City. Try this best accommodation,

Best hotels in srinagar

Family Tour Package For Kashmir

Best Family Hotels in Srinagar

Cheapest Kashmir Group Tour Packages

Post a Comment