ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA

In 1979, three years after Mao’s death, a one-child policy was introduced to control China’s burgeoning population and reduce the strain on scarce resources. According to the policy as it was most commonly enforced, a couple was allowed to have one child. If that child turned out be a girl, they were allowed to have a second child. After the second child, they were not allowed to have any more children. In some places though couples were only allowed to have one child regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. This policy is still in effect today. It is unusual for a family to have two sons.

In 1979, three years after Mao’s death, a one-child policy was introduced to control China’s burgeoning population and reduce the strain on scarce resources. According to the policy as it was most commonly enforced, a couple was allowed to have one child. If that child turned out be a girl, they were allowed to have a second child. After the second child, they were not allowed to have any more children. In some places though couples were only allowed to have one child regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. This policy is still in effect today. It is unusual for a family to have two sons. Under the one-child program, a sophisticated system rewarded those who observed the policy and penalized those who did not. Couples with only one child were given a "one-child certificate" entitling them to such benefits as cash bonuses, longer maternity leave, better child care, and preferential housing assignments. In return, they were required to pledge that they would not have more children. In the countryside, there was great pressure to adhere to the one-child limit. Because the rural population accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total, the effectiveness of the one-child policy in rural areas was considered the key to the success or failure of the program as a whole. [Source: Library of Congress]

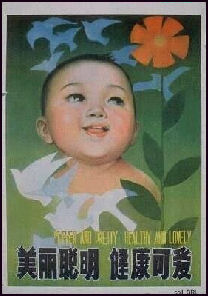

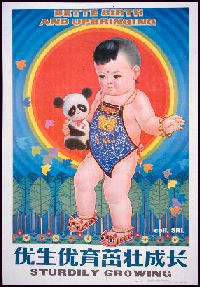

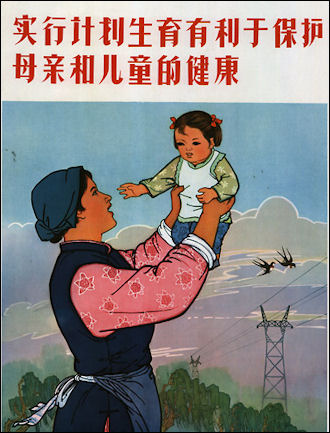

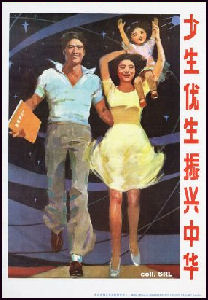

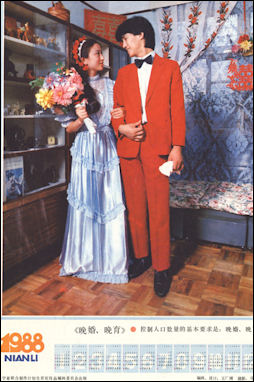

Under the one-child program, a sophisticated system rewarded those who observed the policy and penalized those who did not. Couples with only one child were given a "one-child certificate" entitling them to such benefits as cash bonuses, longer maternity leave, better child care, and preferential housing assignments. In return, they were required to pledge that they would not have more children. In the countryside, there was great pressure to adhere to the one-child limit. Because the rural population accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total, the effectiveness of the one-child policy in rural areas was considered the key to the success or failure of the program as a whole. [Source: Library of Congress] Posters promoting China's one-child policy can be seen all over China. One, with the slogan "China Needs Family Planning" shows a Communist official praising the proud parents of one baby girl. Another one, with the slogan "Late Marriage and Childbirth Are Worthy," shows an old gray-haired woman with a newborn baby. Another reads: “Have Fewer, Better Children to Create Prosperity for the Next Generation.”

Posters promoting China's one-child policy can be seen all over China. One, with the slogan "China Needs Family Planning" shows a Communist official praising the proud parents of one baby girl. Another one, with the slogan "Late Marriage and Childbirth Are Worthy," shows an old gray-haired woman with a newborn baby. Another reads: “Have Fewer, Better Children to Create Prosperity for the Next Generation.” Slogans such as “Have Fewer Children Live Better Lives” and "Stabilize Family Planning and Create a Brighter Future” are painted on roadside buildings in rural areas. Some crude family planning slogans such “Raise Fewer Babies, But More Piggies” and “One More Baby Means One More Tomb” and "If you give birth to extra children, your family will be ruined" were banned in August 2007 because of rural anger about the slogans and the policy behind them.

Slogans such as “Have Fewer Children Live Better Lives” and "Stabilize Family Planning and Create a Brighter Future” are painted on roadside buildings in rural areas. Some crude family planning slogans such “Raise Fewer Babies, But More Piggies” and “One More Baby Means One More Tomb” and "If you give birth to extra children, your family will be ruined" were banned in August 2007 because of rural anger about the slogans and the policy behind them. The one-child policy actually only covers about 35 percent of Chinese, mostly those living in urban areas. The conventional wisdom in China has been that controlling China's population serves the interest of the whole society and that sacrificing individual interests for those of the masses is justifiable. The one-child policy was introduced around the same time as the Deng economic reforms. An unexpected result of these reforms has been the creation of demand for more children to supply labor to increase food production and make more profit.

The one-child policy actually only covers about 35 percent of Chinese, mostly those living in urban areas. The conventional wisdom in China has been that controlling China's population serves the interest of the whole society and that sacrificing individual interests for those of the masses is justifiable. The one-child policy was introduced around the same time as the Deng economic reforms. An unexpected result of these reforms has been the creation of demand for more children to supply labor to increase food production and make more profit. Also See Separate Articles: 1) ABDUCTED CHILDREN, GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS AND THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA and 2) REFORMING THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA

Also See Separate Articles: 1) ABDUCTED CHILDREN, GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS AND THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA and 2) REFORMING THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA Good Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Family Planning in China china.org.cn ; New England Journal of Medicine articlenejm.org ; One Child policy articles harker.org Links in this Website: POPULATION IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; BIRTH CONTROL IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; PREFERENCE FOR BOYS Factsanddetails.com/China ; THE BRIDE SHORTAGE IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China

Good Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Family Planning in China china.org.cn ; New England Journal of Medicine articlenejm.org ; One Child policy articles harker.org Links in this Website: POPULATION IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; BIRTH CONTROL IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; PREFERENCE FOR BOYS Factsanddetails.com/China ; THE BRIDE SHORTAGE IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/ChinaSuccess of the One-Child Policy in China

The one-child policy has been spectacularly successful in reducing population growth, particularly in the cities (reliable figures are harder to come by in the countryside). In 1970 the average woman in China had almost six (5.8) children, now she has about two. The most dramatic changes took place between 1970 and 1980 when the birthrate dropped from 44 per 1000 to 18 per 1,000. Demographers have stated that the ideal birthrate rate for China is 16.7 per 1,000, or 1.7 children per family.

The one-child policy has been spectacularly successful in reducing population growth, particularly in the cities (reliable figures are harder to come by in the countryside). In 1970 the average woman in China had almost six (5.8) children, now she has about two. The most dramatic changes took place between 1970 and 1980 when the birthrate dropped from 44 per 1000 to 18 per 1,000. Demographers have stated that the ideal birthrate rate for China is 16.7 per 1,000, or 1.7 children per family. One Chinese official said the one-child policy has prevented 300 million births, the equivalent of the population of Europe. The reduction of population has helped pull people out of poverty and been a factor in China’s phenomenal economic growth. One way the government records progress in its birth control programs is by monitoring the "first baby" rate—the proportion of first babies among total births. In the city of Chengdu in Sichuan for a while the first baby rate was reportedly 97 percent.

One Chinese official said the one-child policy has prevented 300 million births, the equivalent of the population of Europe. The reduction of population has helped pull people out of poverty and been a factor in China’s phenomenal economic growth. One way the government records progress in its birth control programs is by monitoring the "first baby" rate—the proportion of first babies among total births. In the city of Chengdu in Sichuan for a while the first baby rate was reportedly 97 percent. Some argue that economic prosperity has done as much as the one-child policy to shrink population growth. As costs and the expense of having children in urban areas rise, and the benefits of children as labor sources shrink many couples opt not to have children. Susan Greenhalgh, a China policy expert at the University of California in Irvine, told Reuters, “Rapid socioeconomic development has largely taken care of the problem of rapid population.” Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, have lower birthrates without coercive measures, as people marry later and move into smaller homes. Birthrates are also very low in Europe.

Some argue that economic prosperity has done as much as the one-child policy to shrink population growth. As costs and the expense of having children in urban areas rise, and the benefits of children as labor sources shrink many couples opt not to have children. Susan Greenhalgh, a China policy expert at the University of California in Irvine, told Reuters, “Rapid socioeconomic development has largely taken care of the problem of rapid population.” Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, have lower birthrates without coercive measures, as people marry later and move into smaller homes. Birthrates are also very low in Europe. Even without state intervention, there were compelling reasons for urban couples to limit the family to a single child. Raising a child required a significant portion of family income, and in the cities a child did not become an economic asset until he or she entered the work force at age sixteen. Couples with only one child were given preferential treatment in housing allocation. In addition, because city dwellers who were employed in state enterprises received pensions after retirement, the sex of their first child was less important to them than it was to those in rural areas. [Source: Library of Congress]

Even without state intervention, there were compelling reasons for urban couples to limit the family to a single child. Raising a child required a significant portion of family income, and in the cities a child did not become an economic asset until he or she entered the work force at age sixteen. Couples with only one child were given preferential treatment in housing allocation. In addition, because city dwellers who were employed in state enterprises received pensions after retirement, the sex of their first child was less important to them than it was to those in rural areas. [Source: Library of Congress]Population Control in China Under Mao

The Chinese have made great strides in reducing their population through birth control. But that has not always been the case. Mao did nothing to reduce China's expanding population, which doubled under his leadership. He believed that birth control was a capitalist plot to weaken the country and make it vulnerable to attack. He also liked to say, "every mouth comes with two hands attached." For a while Mao urged Chinese to have lots of children to support his “human wave” defense policy when he feared attack from the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Chinese have made great strides in reducing their population through birth control. But that has not always been the case. Mao did nothing to reduce China's expanding population, which doubled under his leadership. He believed that birth control was a capitalist plot to weaken the country and make it vulnerable to attack. He also liked to say, "every mouth comes with two hands attached." For a while Mao urged Chinese to have lots of children to support his “human wave” defense policy when he feared attack from the United States and the Soviet Union. Soon after taking power in 1949 Mao declared: ‘Of all things in the world, people are the most precious.’ He condemned birth control and banned the import of contraceptives. He then proceeded to kill lots of people through vicious crackdowns on landlords and counter-revolutionaries, through the use of human-wave warfare in North Korea and through failed experiments like the Great Leap Forward.

Soon after taking power in 1949 Mao declared: ‘Of all things in the world, people are the most precious.’ He condemned birth control and banned the import of contraceptives. He then proceeded to kill lots of people through vicious crackdowns on landlords and counter-revolutionaries, through the use of human-wave warfare in North Korea and through failed experiments like the Great Leap Forward. Over time the liabilities of a large, rapidly growing population soon became apparent. For one year, starting in August 1956, vigorous propaganda support was given to the Ministry of Public Health's mass birth control efforts. These efforts, however, had little impact on fertility. After the interval of the Great Leap Forward, Chinese leaders again saw rapid population growth as an obstacle to development, and their interest in birth control revived. In the early 1960s, propaganda, somewhat more muted than during the first campaign, emphasized the virtues of late marriage. Birth control offices were set up in the central government and some provinciallevel governments in 1964. The second campaign was particularly successful in the cities, where the birth rate was cut in half during the 1963-66 period. The chaos of the Cultural Revolution brought the program to a halt, however. [Source: Library of Congress]

Over time the liabilities of a large, rapidly growing population soon became apparent. For one year, starting in August 1956, vigorous propaganda support was given to the Ministry of Public Health's mass birth control efforts. These efforts, however, had little impact on fertility. After the interval of the Great Leap Forward, Chinese leaders again saw rapid population growth as an obstacle to development, and their interest in birth control revived. In the early 1960s, propaganda, somewhat more muted than during the first campaign, emphasized the virtues of late marriage. Birth control offices were set up in the central government and some provinciallevel governments in 1964. The second campaign was particularly successful in the cities, where the birth rate was cut in half during the 1963-66 period. The chaos of the Cultural Revolution brought the program to a halt, however. [Source: Library of Congress] In the 1970s Mao began to come around to the threats posed by too many people. He began encouraged a policy of ‘late, long and few’ and coined the slogan: ‘One is good, two is OK, three is too many.’ In the years after his death, China began experimenting with the one-child policy. In 1972 and 1973 the party mobilized its resources for a nationwide birth control campaign administered by a group in the State Council. Committees to oversee birth control activities were established at all administrative levels and in various collective enterprises. This extensive and seemingly effective network covered both the rural and the urban population. In urban areas public security headquarters included population control sections. In rural areas the country's "barefoot doctors" distributed information and contraceptives to people's commun members. By 1973 Mao Zedong was personally identified with the family planning movement, signifying a greater leadership commitment to controlled population growth than ever before. Yet until several years after Mao's death in 1976, the leadership was reluctant to put forth directly the rationale that population control was necessary for economic growth and improved living standards. [Ibid]

In the 1970s Mao began to come around to the threats posed by too many people. He began encouraged a policy of ‘late, long and few’ and coined the slogan: ‘One is good, two is OK, three is too many.’ In the years after his death, China began experimenting with the one-child policy. In 1972 and 1973 the party mobilized its resources for a nationwide birth control campaign administered by a group in the State Council. Committees to oversee birth control activities were established at all administrative levels and in various collective enterprises. This extensive and seemingly effective network covered both the rural and the urban population. In urban areas public security headquarters included population control sections. In rural areas the country's "barefoot doctors" distributed information and contraceptives to people's commun members. By 1973 Mao Zedong was personally identified with the family planning movement, signifying a greater leadership commitment to controlled population growth than ever before. Yet until several years after Mao's death in 1976, the leadership was reluctant to put forth directly the rationale that population control was necessary for economic growth and improved living standards. [Ibid] The "Later, Longer, Fewer" policy that is the cornerstone of China's birth control program was put into effect in 1976, around the same time that Mao died. It encouraged couples to get married later, wait longer to have children, and have fewer children, preferably one. The program forced married couples to sign statements that obligated them to one child. Women who had abortions were given free vacations.

The "Later, Longer, Fewer" policy that is the cornerstone of China's birth control program was put into effect in 1976, around the same time that Mao died. It encouraged couples to get married later, wait longer to have children, and have fewer children, preferably one. The program forced married couples to sign statements that obligated them to one child. Women who had abortions were given free vacations.Birth Patterns Before the One-Child Policy

According to Chinese government statistics, the crude birth rate followed five distinct patterns from 1949 to 1982. It remained stable from 1949 to 1954, varied widely from 1955 to 1965, experienced fluctuations between 1966 and 1969, dropped sharply in the late 1970s, and increased from 1980 to 1981. Between 1970 and 1980, the crude birth rate dropped from 36.9 per 1,000 to 17.6 per 1,000. The government attributed this dramatic decline in fertility to the wan xi shao (later marriages, longer intervals between births, and fewer children) birth control campaign. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to Chinese government statistics, the crude birth rate followed five distinct patterns from 1949 to 1982. It remained stable from 1949 to 1954, varied widely from 1955 to 1965, experienced fluctuations between 1966 and 1969, dropped sharply in the late 1970s, and increased from 1980 to 1981. Between 1970 and 1980, the crude birth rate dropped from 36.9 per 1,000 to 17.6 per 1,000. The government attributed this dramatic decline in fertility to the wan xi shao (later marriages, longer intervals between births, and fewer children) birth control campaign. [Source: Library of Congress] “However, elements of socioeconomic change, such as increased employment of women in both urban and rural areas and reduced infant mortality (a greater percentage of surviving children would tend to reduce demand for additional children), may have played some role. To the dismay of authorities, the birth rate increased in both 1981 and 1982 to a level of 21 per 1,000, primarily as a result of a marked rise in marriages and first births. The rise was an indication of problems with the one-child policy of 1979. Chinese sources, however, indicated that the birth rate decreased to 17.8 in 1985 and remained relatively constant thereafter. [Ibid]

“However, elements of socioeconomic change, such as increased employment of women in both urban and rural areas and reduced infant mortality (a greater percentage of surviving children would tend to reduce demand for additional children), may have played some role. To the dismay of authorities, the birth rate increased in both 1981 and 1982 to a level of 21 per 1,000, primarily as a result of a marked rise in marriages and first births. The rise was an indication of problems with the one-child policy of 1979. Chinese sources, however, indicated that the birth rate decreased to 17.8 in 1985 and remained relatively constant thereafter. [Ibid] “In urban areas, the housing shortage may have been at least partly responsible for the decreased birth rate. Also, the policy in force during most of the 1960s and the early 1970s of sending large numbers of high school graduates to the countryside deprived cities of a significant proportion of persons of childbearing age and undoubtedly had some effect on birth rates. [Ibid]

“In urban areas, the housing shortage may have been at least partly responsible for the decreased birth rate. Also, the policy in force during most of the 1960s and the early 1970s of sending large numbers of high school graduates to the countryside deprived cities of a significant proportion of persons of childbearing age and undoubtedly had some effect on birth rates. [Ibid] “Primarily for economic reasons, rural birth rates tended to decline less than urban rates. The right to grow and sell agricultural products for personal profit and the lack of an oldage welfare system were incentives for rural people to produce many children, especially sons, for help in the fields and for support in old age. Because of these conditions, it is unclear to what degree propaganda and education improvements had been able to erode traditional values favoring large families

“Primarily for economic reasons, rural birth rates tended to decline less than urban rates. The right to grow and sell agricultural products for personal profit and the lack of an oldage welfare system were incentives for rural people to produce many children, especially sons, for help in the fields and for support in old age. Because of these conditions, it is unclear to what degree propaganda and education improvements had been able to erode traditional values favoring large families2010 Census and One-Child Policy

“A challenge for the census-takers are children born in violation of the country's urban one-child policy, many of whom are unregistered and therefore have no legal identity,” Anita Chang of AP wrote. “They could number in the millions. The government has said it would lower or waive the hefty penalty fees required for those children to obtain identity cards, though so far there has not been much response to the limited amnesty.” [Source: Anita Chang, AP, September 3,2010]

“A challenge for the census-takers are children born in violation of the country's urban one-child policy, many of whom are unregistered and therefore have no legal identity,” Anita Chang of AP wrote. “They could number in the millions. The government has said it would lower or waive the hefty penalty fees required for those children to obtain identity cards, though so far there has not been much response to the limited amnesty.” [Source: Anita Chang, AP, September 3,2010] Many say they have been reassured by the government's declaration that information cannot be used to levy fines, which often run as high as six times an annual income for extra births."This is only about statistics, but people are worried that they could get fined for having an extra child and they'll avoid the census," Duan Chengrong, head of the population department at Renmin University told AP. "Like in the U.S., the Chinese these days are paying more attention to their privacy."

Many say they have been reassured by the government's declaration that information cannot be used to levy fines, which often run as high as six times an annual income for extra births."This is only about statistics, but people are worried that they could get fined for having an extra child and they'll avoid the census," Duan Chengrong, head of the population department at Renmin University told AP. "Like in the U.S., the Chinese these days are paying more attention to their privacy."Bureaucracy and Population Control in China

The National Population and Family Planning Commission runs the one-child policy and monitors the child bearing habits of the Chinese masses. It is comprised of 300,000 full-time paid family-planning workers and 80 million volunteers, who are notorious for being nosey, intrusive and using social pressure to meet its goals and quotas. Chinese women have to obtain a permit to have a child. If a woman is pregnant and she already has children she is often pressured into having an abortion. Special bonuses are given to men and women that have their tubes tied. Local officials are often evaluated in how well they meet their population quotas. Communist Party cadres can be denied bonuses and blocked from promotions if there are excess births in their jurisdictions.

The National Population and Family Planning Commission runs the one-child policy and monitors the child bearing habits of the Chinese masses. It is comprised of 300,000 full-time paid family-planning workers and 80 million volunteers, who are notorious for being nosey, intrusive and using social pressure to meet its goals and quotas. Chinese women have to obtain a permit to have a child. If a woman is pregnant and she already has children she is often pressured into having an abortion. Special bonuses are given to men and women that have their tubes tied. Local officials are often evaluated in how well they meet their population quotas. Communist Party cadres can be denied bonuses and blocked from promotions if there are excess births in their jurisdictions. “In rural areas the day-to-day work of family planning is done by cadres at the team and brigade levels who were responsible for women's affairs and by health workers. Every village has a family planning committee and in some, women of childbearing age are required to have pregnancy tests every three months. In the 1980s the women's team leader made regular household visits to keep track of the status of each family under her jurisdiction and collected information on which women were using contraceptives, the methods used, and which had become pregnant. She then reported to the brigade women's leader, who documented the information and took it to a monthly meeting of the commune birth-planning committee. According to reports, ceilings or quotas had to be adhered to; to satisfy these cutoffs, unmarried young people were persuaded to postpone marriage, couples without children were advised to "wait their turn," women with unauthorized pregnancies were pressured to have abortions, and those who already had children were urged to use contraception or undergo sterilization. Couples with more than one child were exhorted to be sterilized. [Source: Library of Congress]

“In rural areas the day-to-day work of family planning is done by cadres at the team and brigade levels who were responsible for women's affairs and by health workers. Every village has a family planning committee and in some, women of childbearing age are required to have pregnancy tests every three months. In the 1980s the women's team leader made regular household visits to keep track of the status of each family under her jurisdiction and collected information on which women were using contraceptives, the methods used, and which had become pregnant. She then reported to the brigade women's leader, who documented the information and took it to a monthly meeting of the commune birth-planning committee. According to reports, ceilings or quotas had to be adhered to; to satisfy these cutoffs, unmarried young people were persuaded to postpone marriage, couples without children were advised to "wait their turn," women with unauthorized pregnancies were pressured to have abortions, and those who already had children were urged to use contraception or undergo sterilization. Couples with more than one child were exhorted to be sterilized. [Source: Library of Congress] At the bottom of the bureaucracy are millions of neighborhood committees which have to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn are under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow birth control guidelines laid out by the Central Chinese government.

At the bottom of the bureaucracy are millions of neighborhood committees which have to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn are under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow birth control guidelines laid out by the Central Chinese government. If neighborhood, street or village committees are unsuccessful in dissuading a couple from having a child, community "units" at the husband's and wife's work place are called in to pressure the couple, sometimes by reducing wages, taking away bonuses or threatening unemployment. Community units are also called in if a couple is thinking about getting divorced.

If neighborhood, street or village committees are unsuccessful in dissuading a couple from having a child, community "units" at the husband's and wife's work place are called in to pressure the couple, sometimes by reducing wages, taking away bonuses or threatening unemployment. Community units are also called in if a couple is thinking about getting divorced.Family Planning Officials

The officials who work in the local family offices are often members of the Communist Party. They have broad powers to order abortions and sterilizations and impose heavy fines euphemistically called “social service expenditures,” which are often important sources of income for local governments in rural areas.

The officials who work in the local family offices are often members of the Communist Party. They have broad powers to order abortions and sterilizations and impose heavy fines euphemistically called “social service expenditures,” which are often important sources of income for local governments in rural areas. Couples are supposed to get a permit before they even conceive a child. To be eligible couples must have a marriage certificates and have their residency permits in order. Women must be at least 20 and men 24.

Couples are supposed to get a permit before they even conceive a child. To be eligible couples must have a marriage certificates and have their residency permits in order. Women must be at least 20 and men 24. Old legal scholar in Beijing told the Los Angeles Times, “the family planing people are even more powerful than the Ministry of Public Security.”

Old legal scholar in Beijing told the Los Angeles Times, “the family planing people are even more powerful than the Ministry of Public Security.” Villagers who can’t pay the fines complain that family planning officials confiscate their pigs and cattle and ransack their homes and even seize their children. Sometimes officials make regular visits looking for illegal children. “We were always terrified of them,” one villager told the Los Angeles Times.

Villagers who can’t pay the fines complain that family planning officials confiscate their pigs and cattle and ransack their homes and even seize their children. Sometimes officials make regular visits looking for illegal children. “We were always terrified of them,” one villager told the Los Angeles Times.Rewards for One Child and Punishments for Extra Children

Marry Late poster

Parents who have only one child get a "one-child glory certificate," which entitles them to economic benefits such as an extra month's salary every year until the child is 14. Among the other benefits for one child families are higher wages, interest-free loans, retirement funds, cheap fertilizer, better housing, better health care, and priority in school enrollment. Women who delay marriage until after they are 25 receive benefits such as an extended maternity leave when they finally get pregnant. These privileges are taken away if the couple decides to have an extra child. Promises for new housing often are not kept because of housing shortages.

Parents who have only one child get a "one-child glory certificate," which entitles them to economic benefits such as an extra month's salary every year until the child is 14. Among the other benefits for one child families are higher wages, interest-free loans, retirement funds, cheap fertilizer, better housing, better health care, and priority in school enrollment. Women who delay marriage until after they are 25 receive benefits such as an extended maternity leave when they finally get pregnant. These privileges are taken away if the couple decides to have an extra child. Promises for new housing often are not kept because of housing shortages. The one-child program theoretically is voluntary, but the government imposes punishments and heavy fines on people who don't follow the rules. Parents with extra children can be fined, depending on the region, from $370 to $12,800 (many times the average annual income for many ordinary Chinese). If the fine is not paid sometimes the couples land is taken away, their house is destroyed, they lose their jobs or the child is not allowed to attend school.

The one-child program theoretically is voluntary, but the government imposes punishments and heavy fines on people who don't follow the rules. Parents with extra children can be fined, depending on the region, from $370 to $12,800 (many times the average annual income for many ordinary Chinese). If the fine is not paid sometimes the couples land is taken away, their house is destroyed, they lose their jobs or the child is not allowed to attend school. Sometimes the punishments seem more than a little over the top. In the 1980s a woman from Shanghai named Mao Hengfeng, who got pregnant with her second child, was fired from her job, forced to undergo an abortion and was sent to a psychiatric hospital and was still in a labor camp the early 2000s, There were reports that she had been tortured.

Sometimes the punishments seem more than a little over the top. In the 1980s a woman from Shanghai named Mao Hengfeng, who got pregnant with her second child, was fired from her job, forced to undergo an abortion and was sent to a psychiatric hospital and was still in a labor camp the early 2000s, There were reports that she had been tortured. Into the mid 2000s, authorities in Shandong raided the homes of families with extra children, demanding that parents with second children get sterilized and women pregnant with their third children get abortions. If a family tried to hide their relatives were thrown in jail until the escapees surrendered. One woman who said she had permission for a second child told the Washington Post she was hustled into a white van, taken to clinic, physically forced to sign a form and was given a sterilization operation that took only 10 minutes.

Into the mid 2000s, authorities in Shandong raided the homes of families with extra children, demanding that parents with second children get sterilized and women pregnant with their third children get abortions. If a family tried to hide their relatives were thrown in jail until the escapees surrendered. One woman who said she had permission for a second child told the Washington Post she was hustled into a white van, taken to clinic, physically forced to sign a form and was given a sterilization operation that took only 10 minutes. Another women told the Washington Post several of her relatives were thrown in jail when she was seven months pregnant and were denied food and threatened with torture and told they wouldn’t be released until the woman had an abortion. After she turned herself in, a doctor inserted a needle into her uterus. Twenty-four hours later she delivered a dead fetus. Another woman was forced to undergo a botched sterilization that left her with difficulty walking.

Another women told the Washington Post several of her relatives were thrown in jail when she was seven months pregnant and were denied food and threatened with torture and told they wouldn’t be released until the woman had an abortion. After she turned herself in, a doctor inserted a needle into her uterus. Twenty-four hours later she delivered a dead fetus. Another woman was forced to undergo a botched sterilization that left her with difficulty walking. Even high level officials are not immune from the policies. In April 2007, a Communist Party official in Yulin in Shanxi was fired for having too many children—three daughters with his wife and a son and daughter with his mistress.Some parents who broke the one child policy have were required to pay their fine with grain: 200 kilograms of unmilled rice

Even high level officials are not immune from the policies. In April 2007, a Communist Party official in Yulin in Shanxi was fired for having too many children—three daughters with his wife and a son and daughter with his mistress.Some parents who broke the one child policy have were required to pay their fine with grain: 200 kilograms of unmilled rice Sometimes the fees for a second child are jacked up for couples with high incomes. One woman who earned $127,000 a year with her husband told The Times she was told her fees for a second child would between $44,650 and $76,540. She ended up paying $5,000 to special agent to give birth in Hong Kong, where the one-child policy does not apply. [Ibid] Many demographers argue the policy has worsened the country's aging crisis by limiting the size of the young labour pool that must support the large baby boom generation as it retires. They say it has contributed to the imbalanced sex ratio by encouraging families to abort baby girls, preferring to try for a male heir. The government recognises those problems and has tried to address them by boosting social services for the elderly. It has also banned sex-selective abortion and rewarded rural families whose only child is a girl. [Source: Associated Press, October 31, 2012]

Sometimes the fees for a second child are jacked up for couples with high incomes. One woman who earned $127,000 a year with her husband told The Times she was told her fees for a second child would between $44,650 and $76,540. She ended up paying $5,000 to special agent to give birth in Hong Kong, where the one-child policy does not apply. [Ibid] Many demographers argue the policy has worsened the country's aging crisis by limiting the size of the young labour pool that must support the large baby boom generation as it retires. They say it has contributed to the imbalanced sex ratio by encouraging families to abort baby girls, preferring to try for a male heir. The government recognises those problems and has tried to address them by boosting social services for the elderly. It has also banned sex-selective abortion and rewarded rural families whose only child is a girl. [Source: Associated Press, October 31, 2012]$100,000 Loan for Chinese Who Abide by the On-Child Policy

In some cases families that obey the one-child policy rules get generous loans. Reporting from Xiamen, Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “A 6-year-old girl with a bob haircut sat alone on an enormous wraparound couch, dwarfed by the living room furniture and a giant flat-screen TV. As she flicked the remote in search of cartoons, her parents pointed proudly to the recessed lighting and high ceilings. Then they proceeded with an official tour of their three-story house with white marble floors, oversized windows and a granite entryway flanked by a Corinthian column. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

In some cases families that obey the one-child policy rules get generous loans. Reporting from Xiamen, Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “A 6-year-old girl with a bob haircut sat alone on an enormous wraparound couch, dwarfed by the living room furniture and a giant flat-screen TV. As she flicked the remote in search of cartoons, her parents pointed proudly to the recessed lighting and high ceilings. Then they proceeded with an official tour of their three-story house with white marble floors, oversized windows and a granite entryway flanked by a Corinthian column. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012] All of this was paid for with a $100,000 interest-free loan from the Chinese government, an incentive to keep the family's size "in policy." For these residents of a rapidly developing rural area, that meant sticking to two girls and giving up the chance to have a son. The husband, Zhang Qing Ting, an electrical technician, said living in a modern subdivision for in-policy families beats the usual cramped apartments with no garages. He and his wife, Chen Hui Ping, a factory worker, will also be eligible for cash payments when they retire. [Ibid]

All of this was paid for with a $100,000 interest-free loan from the Chinese government, an incentive to keep the family's size "in policy." For these residents of a rapidly developing rural area, that meant sticking to two girls and giving up the chance to have a son. The husband, Zhang Qing Ting, an electrical technician, said living in a modern subdivision for in-policy families beats the usual cramped apartments with no garages. He and his wife, Chen Hui Ping, a factory worker, will also be eligible for cash payments when they retire. [Ibid] "Many of my friends envy me," Zhang said, mopping sweat from his neck as a dozen local officials and family planning bureaucrats looked on. The couple had been given a day off work to showcase the benefits of their restraint to two foreign journalists. Jin Jing, chairman of Chao Le village, summed up the message: "If you practice family planning, you can get this kind of reward."

"Many of my friends envy me," Zhang said, mopping sweat from his neck as a dozen local officials and family planning bureaucrats looked on. The couple had been given a day off work to showcase the benefits of their restraint to two foreign journalists. Jin Jing, chairman of Chao Le village, summed up the message: "If you practice family planning, you can get this kind of reward."Dilemma for One-Child Families: Where to Spend New Year

During the Chinese New Year hundreds of millions of people pack the trains and highways to return to their home towns. But, Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “ for one particular group — young urban married couples who grew up as only children — the yearly ritual can also mean tough decisions, sometimes-painful arguments and a modern-day test of one of China’s centuries-old family traditions. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, January 18, 2012]

During the Chinese New Year hundreds of millions of people pack the trains and highways to return to their home towns. But, Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “ for one particular group — young urban married couples who grew up as only children — the yearly ritual can also mean tough decisions, sometimes-painful arguments and a modern-day test of one of China’s centuries-old family traditions. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, January 18, 2012] These young couples are part of the generation of only children born during the 34 years of China’s “one-child policy.” Following the typical pattern, they migrated to the larger cities from the outlying provinces to go to university. They stayed for work and then got married. And now they must decide which set of parents to visit. It’s a decision fraught with emotion, especially for China’s growing elderly population, often living alone and far from their children, who historically have been caregivers in a country with little social safety net.

These young couples are part of the generation of only children born during the 34 years of China’s “one-child policy.” Following the typical pattern, they migrated to the larger cities from the outlying provinces to go to university. They stayed for work and then got married. And now they must decide which set of parents to visit. It’s a decision fraught with emotion, especially for China’s growing elderly population, often living alone and far from their children, who historically have been caregivers in a country with little social safety net. “Both of us want to go back to our home to celebrate Chinese New Year,” said Lin Youlan, 30, a government worker who married her husband, Li Haibin, 33, four years ago. “We always fight about this problem.” She is from Chongqing in southwest China, and he is from Shandong, on China’s east coast. They live in Beijing, and they are only children. As the only son, Li is under intense pressure to visit his parents, who are not in good health. “In Shandong province, men must celebrate the Spring Festival with their own families. And the wives should spend the Lunar New Year at their husbands’ homes,” he said. “I worry how others will look at my parents if I don’t go back home every year.”

“Both of us want to go back to our home to celebrate Chinese New Year,” said Lin Youlan, 30, a government worker who married her husband, Li Haibin, 33, four years ago. “We always fight about this problem.” She is from Chongqing in southwest China, and he is from Shandong, on China’s east coast. They live in Beijing, and they are only children. As the only son, Li is under intense pressure to visit his parents, who are not in good health. “In Shandong province, men must celebrate the Spring Festival with their own families. And the wives should spend the Lunar New Year at their husbands’ homes,” he said. “I worry how others will look at my parents if I don’t go back home every year.” Traditionally, the Lunar New Year’s Eve and the first day of the new year were spent at the home of the husband’s parents, and the second day was spent with the wife’s. But in those days, married couples largely came from the same village or town or a relatively short distance apart.

Traditionally, the Lunar New Year’s Eve and the first day of the new year were spent at the home of the husband’s parents, and the second day was spent with the wife’s. But in those days, married couples largely came from the same village or town or a relatively short distance apart. Some Chinese couples try to resolve the annual conflict by visiting both sets of parents. Chen Juan, 29, and her husband, Huang Feilong, 31, met in Beijing through an online dating site. They were are both from Hunan province, from cities about three hours’ drive apart. They got married in 2008 and have spent four Chinese New Years together — three at his parents’ home and one with her family. “We fight about this almost every year,” Chen said. This year, they are dividing the week long holiday in half, the first and most important days with his family, then the remainder with hers. But China’s size — as well as the difficulty of finding bus and train tickets over the holiday period — makes traveling to two sets of parents impractical for many.

Some Chinese couples try to resolve the annual conflict by visiting both sets of parents. Chen Juan, 29, and her husband, Huang Feilong, 31, met in Beijing through an online dating site. They were are both from Hunan province, from cities about three hours’ drive apart. They got married in 2008 and have spent four Chinese New Years together — three at his parents’ home and one with her family. “We fight about this almost every year,” Chen said. This year, they are dividing the week long holiday in half, the first and most important days with his family, then the remainder with hers. But China’s size — as well as the difficulty of finding bus and train tickets over the holiday period — makes traveling to two sets of parents impractical for many.Public Opinion on the One-Child Policy and Reasons for Having Additional Children

A survey by the National Family Planning Commission in China cited in the Chinese press found that women are increasingly keen to have more than one child. “Our research shows that 70.7 percent of women would like to have two or more babies,” said Jiang Fan, vice-minister of the commission said, according to China Daily. “Some mothers think only-children suffer from loneliness and can become spoiled.” The survey said that 83 percent of women wanted a son and a daughter. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 16, 2009]

A survey by the National Family Planning Commission in China cited in the Chinese press found that women are increasingly keen to have more than one child. “Our research shows that 70.7 percent of women would like to have two or more babies,” said Jiang Fan, vice-minister of the commission said, according to China Daily. “Some mothers think only-children suffer from loneliness and can become spoiled.” The survey said that 83 percent of women wanted a son and a daughter. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 16, 2009] The surveys publication may reflect ongoing discussion within the government about how to reform the laws. The authorities are usually keen to play down opposition to the policy. A vice-minister had earlier said officials were carrying out detailed studies into the repercussions of changing the law and that it had become “a big issue among decision makers”. [Ibid]

The surveys publication may reflect ongoing discussion within the government about how to reform the laws. The authorities are usually keen to play down opposition to the policy. A vice-minister had earlier said officials were carrying out detailed studies into the repercussions of changing the law and that it had become “a big issue among decision makers”. [Ibid] Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Nowadays, it's not so much a matter of having a large family to work in the fields. Chinese villagers want one child to go away to work and earn money, another to maintain the family home in the village. As the Chinese countryside goes, Shandong is relatively prosperous with its easy access to Beijing, Tianjin, Qingdao and the oil fields along the coast. Many families are willing to pay the fines, which run up to five times annual income, for an extra baby.” [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2012]

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Nowadays, it's not so much a matter of having a large family to work in the fields. Chinese villagers want one child to go away to work and earn money, another to maintain the family home in the village. As the Chinese countryside goes, Shandong is relatively prosperous with its easy access to Beijing, Tianjin, Qingdao and the oil fields along the coast. Many families are willing to pay the fines, which run up to five times annual income, for an extra baby.” [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2012]Views About Abortion and the One Child Policy in China

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: There has always been a vast and curious gap between the way abortion is perceived in the United States and in China. For years, the Chinese public has looked on, with some confusion, at the fact that it’s a litmus-test issue in America. In China, it is a largely unremarked-upon feature of life, despite growing steadily from 1979, when the government began its policy to curb the growth of the world’s largest population. By 1983, the number of abortions had nearly tripled, to 14.4 million, and, that year, the government relaxed the policy to allow rural families a second child if the first was a girl. But in the years that followed, the one-child policy came to occupy an awkward position in the public consciousness: reviled on a personal level, but passively tolerated on a national level because the blunt fact was that people were glad not to have more people among them, more competition for food and jobs and college admissions. Today, family planning is promoted by a vast system that dispenses contraceptives and keeps track of births, but it mainly focusses on married couples. Partly because contraceptives are not as actively promoted to unmarried people, hospitals have described an uptick in voluntary abortions by single women in recent years, and services are advertised as “Safe & Easy A+.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, Japan 15, 2012]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: There has always been a vast and curious gap between the way abortion is perceived in the United States and in China. For years, the Chinese public has looked on, with some confusion, at the fact that it’s a litmus-test issue in America. In China, it is a largely unremarked-upon feature of life, despite growing steadily from 1979, when the government began its policy to curb the growth of the world’s largest population. By 1983, the number of abortions had nearly tripled, to 14.4 million, and, that year, the government relaxed the policy to allow rural families a second child if the first was a girl. But in the years that followed, the one-child policy came to occupy an awkward position in the public consciousness: reviled on a personal level, but passively tolerated on a national level because the blunt fact was that people were glad not to have more people among them, more competition for food and jobs and college admissions. Today, family planning is promoted by a vast system that dispenses contraceptives and keeps track of births, but it mainly focusses on married couples. Partly because contraceptives are not as actively promoted to unmarried people, hospitals have described an uptick in voluntary abortions by single women in recent years, and services are advertised as “Safe & Easy A+.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, Japan 15, 2012] That ambivalence explained, in part, why people in China never rallied as actively as you might expect around Chen Guangcheng, the blind lawyer who was persecuted by local officials for trying to stop forced abortions and sterilizations, eventually taking refuge in the American Embassy, and going to the United States with his family as a visiting scholar at N.Y.U. It was also one reason why Chen’s fervent embrace by American conservatives, who saw him as a comrade-in-arms in the abortion debate, has always been a curious fit. His campaign to protect the rights of women and individuals from abuse by an authoritarian state shares more philosophical D.N.A. with liberalism than with the religious right. In that sense, Chen has always attracted an odd alliance of admirers, and I’ve half-wondered if there won’t come a day when he will point out in his relentlessly honest way that, actually, he is not in favor of policy that deprives people of control over their own bodies. [Ibid]

That ambivalence explained, in part, why people in China never rallied as actively as you might expect around Chen Guangcheng, the blind lawyer who was persecuted by local officials for trying to stop forced abortions and sterilizations, eventually taking refuge in the American Embassy, and going to the United States with his family as a visiting scholar at N.Y.U. It was also one reason why Chen’s fervent embrace by American conservatives, who saw him as a comrade-in-arms in the abortion debate, has always been a curious fit. His campaign to protect the rights of women and individuals from abuse by an authoritarian state shares more philosophical D.N.A. with liberalism than with the religious right. In that sense, Chen has always attracted an odd alliance of admirers, and I’ve half-wondered if there won’t come a day when he will point out in his relentlessly honest way that, actually, he is not in favor of policy that deprives people of control over their own bodies. [Ibid]People Allowed to Have Additional Children in China

Lisu minority baby

In 17 provinces, rural couples are allowed to have a second child if their first is a girl. In the wealthy southern provinces of Guangdong and Hainan, rural couples are allowed two children regardless of the sex of the first. Minority groups such as Tibetans, Miao and Mongols are generally permitted to have three children if their first two are girls.

In 17 provinces, rural couples are allowed to have a second child if their first is a girl. In the wealthy southern provinces of Guangdong and Hainan, rural couples are allowed two children regardless of the sex of the first. Minority groups such as Tibetans, Miao and Mongols are generally permitted to have three children if their first two are girls. Urban couples, who are generally satisfied with small families, are generally restricted to one child. Officials softened the one child policy in rural area where children are needed in the fields and infanticide appears widespread as a result of the preference for boys.

Urban couples, who are generally satisfied with small families, are generally restricted to one child. Officials softened the one child policy in rural area where children are needed in the fields and infanticide appears widespread as a result of the preference for boys. In the Yunnan, where many minorities live, the birth rate was 17 per 1,000 residents, compared to four per 1,000 in Shanghai and five Beijing, and 12 for the country as a whole. So many children are being born in Yunnan that the government is offering cash for school tuition and higher pensions to those who stick with the one child policy.

In the Yunnan, where many minorities live, the birth rate was 17 per 1,000 residents, compared to four per 1,000 in Shanghai and five Beijing, and 12 for the country as a whole. So many children are being born in Yunnan that the government is offering cash for school tuition and higher pensions to those who stick with the one child policy. Parents of a child certified by a doctor as handicapped and couples with both members from single-child homes are also allowed to have an additional child. As children of single-child grow up they will be allowed to have more children.

Parents of a child certified by a doctor as handicapped and couples with both members from single-child homes are also allowed to have an additional child. As children of single-child grow up they will be allowed to have more children. Urban parents are permitted to have two children if the husband and wife were only children.The number of marriages made up of only children is increasing but many are not taking up the option of having a second child. One Beijing couple with a two-year-old son told the Times of London, “It cost more than 35,000 yuan ($5,125) a year just to leave our baby in a kindergarten. Why spend this amount of money on a second?”

Urban parents are permitted to have two children if the husband and wife were only children.The number of marriages made up of only children is increasing but many are not taking up the option of having a second child. One Beijing couple with a two-year-old son told the Times of London, “It cost more than 35,000 yuan ($5,125) a year just to leave our baby in a kindergarten. Why spend this amount of money on a second?” Parents who lost children in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake were allowed to have additional children. In March 2011, a Chinese embassy official said New Zealand should consider compensating the families of students who died in an earthquake in Christchurch. The official said the victims were not only the family’s only children but also future breadwinners, “You can expect how lonely, how desperate they are...not only losing loved ones, but losing almost entirely the major source of economic assistance after retirement.”

Parents who lost children in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake were allowed to have additional children. In March 2011, a Chinese embassy official said New Zealand should consider compensating the families of students who died in an earthquake in Christchurch. The official said the victims were not only the family’s only children but also future breadwinners, “You can expect how lonely, how desperate they are...not only losing loved ones, but losing almost entirely the major source of economic assistance after retirement.”Obstacles to Having a Second Child Under the One-Child Policy Rules

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Chinese policymakers in recent years have seriously discussed relaxing the rules because of an aging population and a gender imbalance in favor of boys. But the seemingly glacial pace of change only makes it more frustrating for those who want more children and don't have time to wait. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2012]

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Chinese policymakers in recent years have seriously discussed relaxing the rules because of an aging population and a gender imbalance in favor of boys. But the seemingly glacial pace of change only makes it more frustrating for those who want more children and don't have time to wait. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2012] “The sense of unfairness is heightened by inconsistency in how the rules are applied. In some rural jurisdictions, people can have a second child if the first is a girl, but only after a waiting period. In other places, a second child is permitted if both parents are single children. Paperwork to obtain permission is cumbersome. The rules are bewildering. The Beijing News carried a story about a young couple who had to collect 50 pages of documents and receive permission from 10 of their nearest neighbors before they could get approval to have a second child. [Ibid]

“The sense of unfairness is heightened by inconsistency in how the rules are applied. In some rural jurisdictions, people can have a second child if the first is a girl, but only after a waiting period. In other places, a second child is permitted if both parents are single children. Paperwork to obtain permission is cumbersome. The rules are bewildering. The Beijing News carried a story about a young couple who had to collect 50 pages of documents and receive permission from 10 of their nearest neighbors before they could get approval to have a second child. [Ibid]One-Child Policy a Surprising Boon for China’s Girls

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Tsinghua University freshman Mia Wang has confidence to spare. Asked what her home city of Benxi in China's far northeastern tip is famous for, she flashes a cool smile and says: "Producing excellence. Like me." A Communist Youth League member at one of China's top science universities, she boasts enviable skills in calligraphy, piano, flute and ping pong.” [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Tsinghua University freshman Mia Wang has confidence to spare. Asked what her home city of Benxi in China's far northeastern tip is famous for, she flashes a cool smile and says: "Producing excellence. Like me." A Communist Youth League member at one of China's top science universities, she boasts enviable skills in calligraphy, piano, flute and ping pong.” [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011] Such gifted young women are increasingly common in China's cities and make up the most educated generation of women in Chinese history. Never have so many been in college or graduate school, and never has their ratio to male students been more balanced. To thank for this, experts say, is three decades of steady Chinese economic growth, heavy government spending on education and a third, surprising, factor: the one-child policy.

Such gifted young women are increasingly common in China's cities and make up the most educated generation of women in Chinese history. Never have so many been in college or graduate school, and never has their ratio to male students been more balanced. To thank for this, experts say, is three decades of steady Chinese economic growth, heavy government spending on education and a third, surprising, factor: the one-child policy. In 1978, women made up only 24.2 percent of the student population at Chinese colleges and universities. By 2009, nearly half of China's full-time undergraduates were women and 47 percent of graduate students were female, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. In India, by comparison, women make up 37.6 percent of those enrolled at institutes of higher education, according to government statistics.

In 1978, women made up only 24.2 percent of the student population at Chinese colleges and universities. By 2009, nearly half of China's full-time undergraduates were women and 47 percent of graduate students were female, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. In India, by comparison, women make up 37.6 percent of those enrolled at institutes of higher education, according to government statistics. Many single-child families are made of two parents and one daughter. With no male heir competing for resources, parents have spent more on their daughters' education and well-being, a groundbreaking shift after centuries of discrimination. "They've basically gotten everything that used to only go to the boys," said Vanessa Fong, a Harvard University professor and expert on China's family planning policy.

Many single-child families are made of two parents and one daughter. With no male heir competing for resources, parents have spent more on their daughters' education and well-being, a groundbreaking shift after centuries of discrimination. "They've basically gotten everything that used to only go to the boys," said Vanessa Fong, a Harvard University professor and expert on China's family planning policy.Girls Growing Up in One-Child Policy Families

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Wang and many of her female classmates grew up with tutors and allowances, after-school classes and laptop computers. Though she is just one generation off the farm, she carries an iPad and a debit card, and shops for the latest fashions online. Her purchases arrive at Tsinghua, where Wang's all-girls dorm used to be jokingly called a "Panda House," because women were so rarely seen on campus. They now make up a third of the student body, up from one-fifth a decade ago. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Wang and many of her female classmates grew up with tutors and allowances, after-school classes and laptop computers. Though she is just one generation off the farm, she carries an iPad and a debit card, and shops for the latest fashions online. Her purchases arrive at Tsinghua, where Wang's all-girls dorm used to be jokingly called a "Panda House," because women were so rarely seen on campus. They now make up a third of the student body, up from one-fifth a decade ago. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011] "In the past, girls were raised to be good wives and mothers," Fong said. "They were going to marry out anyway, so it wasn't a big deal if they didn't want to study." Not so anymore. Fong says today's urban Chinese parents "perceive their daughters as the family's sole hope for the future," and try to help them to outperform their classmates, regardless of gender.

"In the past, girls were raised to be good wives and mothers," Fong said. "They were going to marry out anyway, so it wasn't a big deal if they didn't want to study." Not so anymore. Fong says today's urban Chinese parents "perceive their daughters as the family's sole hope for the future," and try to help them to outperform their classmates, regardless of gender. Things have changed a lot since Wang was born. Wang's birth in the spring of 1992 triggered a family rift that persists to this day. She was a disappointment to her father's parents, who already had one granddaughter from their eldest son. They had hoped for a boy. "Everyone around us had this attitude that boys were valuable, girls were less," Gao Mingxiang, Wang's paternal grandmother, said by way of explanation — but not apology.

Things have changed a lot since Wang was born. Wang's birth in the spring of 1992 triggered a family rift that persists to this day. She was a disappointment to her father's parents, who already had one granddaughter from their eldest son. They had hoped for a boy. "Everyone around us had this attitude that boys were valuable, girls were less," Gao Mingxiang, Wang's paternal grandmother, said by way of explanation — but not apology. Her granddaughter, tall and graceful and dressed in Ugg boots and a sparkly blue top, sat next to her listening, a sour expression on her face. She wasn't shy about showing her lingering bitterness or her eagerness to leave. She agreed to the visit to please her father but refused to stay overnight — despite a four-hour drive each way.

Her granddaughter, tall and graceful and dressed in Ugg boots and a sparkly blue top, sat next to her listening, a sour expression on her face. She wasn't shy about showing her lingering bitterness or her eagerness to leave. She agreed to the visit to please her father but refused to stay overnight — despite a four-hour drive each way.Three-Generation One- Girl Families

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Fong, the Harvard researcher, says that many Chinese households are like this these days: a microcosm of third world and first world cultures clashing. The gulf between Wang and her grandmother seems particularly vast. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Fong, the Harvard researcher, says that many Chinese households are like this these days: a microcosm of third world and first world cultures clashing. The gulf between Wang and her grandmother seems particularly vast. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011] The 77-year-old Gao grew up in Yixian, a poor corn- and wheat-growing county in southern Liaoning province. At 20, she moved less than a mile (about a kilometer) to her new husband's house. She had three children and never dared to dream what life was like outside the village. She remembers rain fell in the living room and a cherished pig was sold, because there wasn't enough money for repairs or feed. She relied on her daughter to help around the house so her two sons could study. "Our kids understood," said Gao, her gray hair pinned back with a bobby pin, her skin chapped by weather, work and age. "All families around here were like that."

The 77-year-old Gao grew up in Yixian, a poor corn- and wheat-growing county in southern Liaoning province. At 20, she moved less than a mile (about a kilometer) to her new husband's house. She had three children and never dared to dream what life was like outside the village. She remembers rain fell in the living room and a cherished pig was sold, because there wasn't enough money for repairs or feed. She relied on her daughter to help around the house so her two sons could study. "Our kids understood," said Gao, her gray hair pinned back with a bobby pin, her skin chapped by weather, work and age. "All families around here were like that." But Wang's mother, Zheng Hong, did not understand. She grew up 300 kilometers (185 miles) away in the steel-factory town of Benxi with two elder sisters and went to vocational college for manufacturing. She lowers her voice to a whisper as she recalls the sting of her in-law's rejection when her daughter was born. "I sort of limited my contact with them after that," Zheng said. "I remember feeling very angry and wronged by them. I decided then that I was going to raise my daughter to be even more outstanding than the boys."

But Wang's mother, Zheng Hong, did not understand. She grew up 300 kilometers (185 miles) away in the steel-factory town of Benxi with two elder sisters and went to vocational college for manufacturing. She lowers her voice to a whisper as she recalls the sting of her in-law's rejection when her daughter was born. "I sort of limited my contact with them after that," Zheng said. "I remember feeling very angry and wronged by them. I decided then that I was going to raise my daughter to be even more outstanding than the boys." They named her Qihua, a pairing of the characters for chess and art — a constant reminder of her parents' hope that she be both clever and artistic. From the age of six, Wang was pushed hard, beginning with ping pong lessons. Competitions were coed, and she beat boys and girls alike, she said. She also learned classical piano and Chinese flute, practiced swimming and ice skating and had tutors for Chinese, English and math. During summer vacations, she competed in English speech contests and started using the name Mia.

They named her Qihua, a pairing of the characters for chess and art — a constant reminder of her parents' hope that she be both clever and artistic. From the age of six, Wang was pushed hard, beginning with ping pong lessons. Competitions were coed, and she beat boys and girls alike, she said. She also learned classical piano and Chinese flute, practiced swimming and ice skating and had tutors for Chinese, English and math. During summer vacations, she competed in English speech contests and started using the name Mia. In high school, Wang had cram sessions for China's college entrance exam that lasted until 10 p.m. Her mother delivered dinners to her at school. She routinely woke up at 6 a.m. to study before class. She had status and expectations her mother and grandmother never knew, a double-edged sword of pampering and pressure. If she'd had a sibling or even the possibility of a sibling one day, the stakes might not have been so high, her studies not so intense.

In high school, Wang had cram sessions for China's college entrance exam that lasted until 10 p.m. Her mother delivered dinners to her at school. She routinely woke up at 6 a.m. to study before class. She had status and expectations her mother and grandmother never knew, a double-edged sword of pampering and pressure. If she'd had a sibling or even the possibility of a sibling one day, the stakes might not have been so high, her studies not so intense. Some, like Wang, are already changing perceptions about what women can achieve. When she dropped by her grandmother's house this spring, the local village chief came by to see her. She was a local celebrity: the first village descendent in memory to make it into Tsinghua University. "Women today, they can go out and do anything," her grandmother said. "They can do big things."

Some, like Wang, are already changing perceptions about what women can achieve. When she dropped by her grandmother's house this spring, the local village chief came by to see her. She was a local celebrity: the first village descendent in memory to make it into Tsinghua University. "Women today, they can go out and do anything," her grandmother said. "They can do big things."Analysis of the One-Child Policy and China’s Girls

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Crediting the one-child policy with improving the lives of women is jarring, given its history and how it's harmed women in other ways. Facing pressure to stay under population quotas, overzealous family planning officials have resorted to forced sterilizations and late-term abortions, sometimes within weeks of delivery, although such practices are illegal. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Crediting the one-child policy with improving the lives of women is jarring, given its history and how it's harmed women in other ways. Facing pressure to stay under population quotas, overzealous family planning officials have resorted to forced sterilizations and late-term abortions, sometimes within weeks of delivery, although such practices are illegal. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011] Beijing-based population expert Yang Juhua has studied enrollment figures and family size and determined that single children in China tend to be the best educated, while those with elder brothers get shortchanged. She was able to make comparisons because China has many loopholes to the one-child rule, including a few cities that have experimented with a two-child policy for decades.

Beijing-based population expert Yang Juhua has studied enrollment figures and family size and determined that single children in China tend to be the best educated, while those with elder brothers get shortchanged. She was able to make comparisons because China has many loopholes to the one-child rule, including a few cities that have experimented with a two-child policy for decades. "Definitely single children are better off, particularly girls,"said Yang, who works at the Center for Population and Development Studies at Renmin University. "If the girl has a brother then she will be disadvantaged. ... If a family has financial constraints, it's more likely that the educational input will go to the sons."

"Definitely single children are better off, particularly girls,"said Yang, who works at the Center for Population and Development Studies at Renmin University. "If the girl has a brother then she will be disadvantaged. ... If a family has financial constraints, it's more likely that the educational input will go to the sons." While her research shows clearly that it's better, education-wise, for girls to be single children, she favors allowing everyone two kids. "I do think the (one-child) policy has improved female well-being to a great extent, but most people want two children so their children can have somebody to play with while they're growing up," said Yang, who herself has a college-age daughter.

While her research shows clearly that it's better, education-wise, for girls to be single children, she favors allowing everyone two kids. "I do think the (one-child) policy has improved female well-being to a great extent, but most people want two children so their children can have somebody to play with while they're growing up," said Yang, who herself has a college-age daughter. While strides have been made in reaching gender parity in education, other inequalities remain. Women remain woefully underrepresented in government, have higher suicide rates than males, often face domestic violence and workplace discrimination and by law must retire at a younger age than men. It remains to be seen whether the new generation of degree-wielding women can alter the balance outside the classroom.

While strides have been made in reaching gender parity in education, other inequalities remain. Women remain woefully underrepresented in government, have higher suicide rates than males, often face domestic violence and workplace discrimination and by law must retire at a younger age than men. It remains to be seen whether the new generation of degree-wielding women can alter the balance outside the classroom. The problem of sex-selected abortion and even female infanticide still exist. Yin Yin Nwe, UNICEF's representative to China, puts it bluntly: The one-child policy brings many benefits for girls "but they have to be born first."